“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.” — Ursula K. Le Guin

I started this Substack last month with an essay about some rather sensitive topics. Exposing my emotions to the world like that was daunting. It demanded vulnerability. But I can’t exactly say it was difficult, as tempting as it might be. Writing is, after all, one of the most vain things a person can do.

Life is extremely short, which renders our time highly valuable. Subtract what is due to our personal and professional obligations each day, and what you have left is what we call our free time—probably the most precious commodity there is. So to write, say, an article or book, and ask that a person devote some of their free time to reading it, is rather bold and betrays a lack of shame. It’s requesting that a person devote potentially hours of their life to consuming your work—hours they’ll never get back. And since they have no idea ahead of time whether it will be worthwhile to them, you’re essentially asking them to take you on trust. That is why writing is a selfish act by nature, and why writers, as a type, play fast and loose with the faith of others.

Writing is at worst an act of public masturbation and at best a cry for help. Every writer knows this whether implicitly or explicitly. The question, then, is why do we write, even though we acknowledge its crudeness? I think there are a few popular reasons why. I’ll list the ones that come to mind.

Reason number one: loneliness. We are lonely creatures by and large. We live in constant fear that others don’t value or respect us; we suspect, moment to moment, that nobody perceives the world the same way we do—parses existence in the same manner. These fears are seemingly confirmed whenever someone doesn’t get a joke we make, or draws a different conclusion than we do from the same information. There are few things we fear more than being alone. What writers do, then, is send out a distress beacon—a call into the void that says, “Hello, is there anybody like me out there?” We pray someone will pick up our broadcast, know how to listen to it, and issue this response: “Stranger, I read you loud and clear. And you know what? Now that I think about it, I am at least a little like you.”

Even if only one person answers our plea, that’s enough. The company of a single individual—even a stranger—is sufficient to confirm that we are indeed human. We are not a faint image superimposed onto the face of the world, although it often feels that way. Rather, we are of it, composed of the same matter and energy. We can touch living things. We’re not ghosts—at least not yet. That’s what we discover when someone enjoys our writing.

That brings me to my second reason: mortality. This is closely related to the first. We become, it seems, more mortal all the time. As we age, we come to learn that the people around us are dynamic—subject to changes in appearance, temperament, and status as living or dead. Eventually, most of us extend this to ourselves. We learn or are taught that tomorrow is never promised. This has an effect on people, often spurring erratic behaviors. One such behavior is writing, or any creative pursuit. By producing a creative work and releasing it to the world, we hedge our bets against eternity. We hope what we have created will outlive us.

Naturally, we don’t expect it to. We’re vain, but not that vain. We understand that we inhabit a universe where even the sun and stars have life spans. If these celestial objects will someday grow cold, then our words stand no chance. But we are equally aware that there are writers who, by talent or circumstance, are still read long after death—even those who were unknown in their own era. The chance of becoming one of those writers is low, but never zero. We are also aware that our souls are so much more well-built than our bodies, which, like a cheap pair of shoes, begin to disintegrate as soon as we put them on. They, not our bodies, are the representatives of our true selves. Creativity—a task by which we expose our souls—then becomes our way of leaving evidence of ourselves. Though this evidence will too dissipate one day, it will certainly last longer than our flesh, and represent us better than our bones ever could.

Third in my list of reasons is persuasion. Let’s face it—we like our opinions. We like them so much that we structure our lives around them, or at least attempt to. We even try, a little or a lot, to reproduce them in others. We want others to believe what we believe. There’s no shame in it. It’s natural—it’s the way culture is made. Writers attempt to communicate an opinion, confirm its strength, and convince others to take it on as if it were their own. This is most evident in, but not solely limited to, political writing. All writing communicates a conviction and a request for the reader to consider it. Oftentimes it’s overt, but sometimes, it lies in the unsaid: in omission, in implication, or in context.

I’ve written about these motivations as though they were separate, and the fact that I’ve been able to tells me they are. But I also believe they share a common goal, so you can think of them as unified in that sense. Each aims to produce good writing. Good writing, in turn, aims to fulfill a function—the same function as all passions. That is, the function of navigating our discontent.

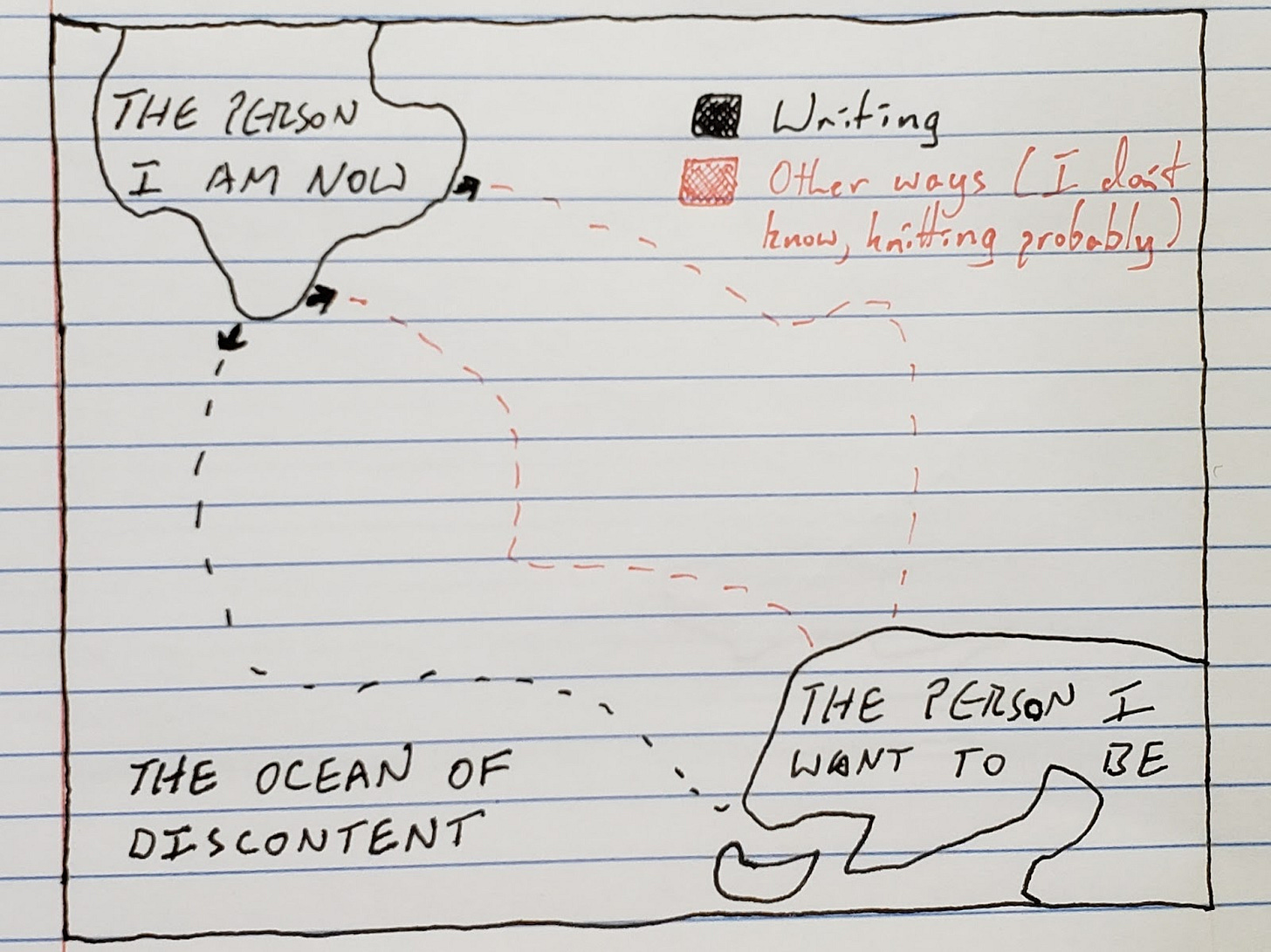

An ocean exists in the life of every person, and our challenge is to sail across it before we die. We start on one landmass and must make it to another. The side we start on, we call The Person I Am. The other shore, that which we endeavor over a lifetime to reach, is known as The Person I Want To Be. Between lies the Ocean of Discontent, which is everything that separates who we are from who we desire to be. To illustrate my point, I’ve drawn you this handy diagram. In the diagram, I have scornfully depicted The Person I Am as resembling Texas. The Person I Want To Be, on the other hand, I have lovingly portrayed as resembling a tortoise eating an orange slice.

There are many ways to cross the Ocean of Discontent. Writing is only one of them. There is also backpacking, making music, raising a family, becoming an astronaut, Formula One racing—the path looks different for every person. For me, though, it looks like writing (and political organizing, and the Dharma, but this essay is about writing).

Writing is a growth practice because it requires the author to lay bare an aspect of themselves to others, and often enough, the first time we reveal something of ourselves to others is also the first time we reveal it to ourselves. When we change, we don’t usually stop to record it and hoist it up onto the taxonomy of our personal evolution (unless, for example, you’re counting the days you’ve been sober). This means that progress often flies under our radar. It isn’t until we undergo a process requiring introspection—such as writing—that we are forced to take inventory of ourselves. Who am I? What do I think is important? What do I believe is true? These are questions we rarely ask ourselves unless prompted by the job at hand. Sometimes the answer surprises us, and we marvel at having transformed a part of ourselves we feared would weigh us down forever.

To seek refuge from loneliness, to play games with mortality, to seek to persuade another—these are all excellent motivations to write. Writing, in turn, guides us through the choppy waters of dissatisfaction. That isn’t to say that the journey across is linear or well-mapped. It never is. There are plenty of loops, backward turns, and storms to be weathered. I’d say my personal path has resembled, more than anything, a pair of tangled earbuds.

Writing is uniquely important to me because of my record of abysmal communication. It has been one of the chief contributors to my discontent, and therefore the distance between who I am and who I want to be. That is to say, my foot has spent so much time inside my mouth that they’re thinking of going steady. From petty misunderstandings to genuinely hurtful remarks, I’ve been a source of it all. I am guilty of a long line of failures to practice deep listening and loving speech. Relatedly, I’ve always been comically awful at consoling others when they experience harm or misfortune. This is doubly embarrassing once you consider the amount of time I spend wallowing in my own grievances, which is a lot. I know how to say none of the things I want to say, and all of the things I don’t. The things I don’t want to say, I spit out readily and effortlessly, unaccompanied by consciousness. Yet I struggle to say even one ounce of what I really mean, and whenever I try, all I can squeeze out is a wretched and tattered imitation.

They say if you give enough monkeys enough typewriters and enough time, they will eventually write Shakespeare. I guess I’m a little like the monkeys in that respect. I’ve convinced myself that if I just write enough, I’ll eventually learn how to say what I really mean. And if I can finally say what I really mean, then maybe, just maybe, I can finally be who I want to be. If I have to leave behind a trail of incomplete arguments and convoluted metaphors along the way, so be it.

Of course, thinking the right thoughts and communicating them properly is only the beginning. It doesn’t, by itself, amount to achievement. That comes only once I have lived in service of others, my actions propelled by these thoughts. Doing that—and doing it rightly—is something entirely different. But that’s a topic for another day.

What about you? What passions guide you? How do you hope to navigate your discontent? How do you plan to become who you want to be?

Image credit:

George Alfred Avison (excepting attributed paintings from museums), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. (Edited)

In an attempt to answer your questions I'll let you in on something -- I'm little more than a literary magpie. I pick up bits and pieces of other's writing and let them stand in for me. For instance, in response to your meditation on writing and mortality, the works of Shelley come to mind. His poem "Ode to the West Wind" has this to say about the written word:

"Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like wither'd leaves to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguish'd hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawaken'd earth

The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?"

Of course, my professors would often get on me for this form, "Too many block quotes! Too little interpretation!" And it's here, for me, that a deep anxiety wells up. I feel like Dr. Reefy, (from Sherwood Anderson's short story Paper Pills which you can find in Winesburg, Ohio) up in my office above main street with the dusted shut windows filled with cobwebs unable to truly appreciate the world, writing original ideas on slips of paper only to let them harden into little paper pills in my pockets. Never sending my thoughts out into the world and left with the bitter sweetness of sour apples.

I suppose writing this response to your beautiful meditation on writing is an attempt to communicate past the anxieties and the poor form of my writing. I feel compelled because what you say about "abysmal communication" I think rings true to all of us. It's strange how writers block so closely mirrors emotional block isn't it?

Enough of my ramblings.